Uncuff India Episode 10: Dimensions of conflict and peace: visioning a utopian world

January 25, 2024Transcript Sanchi- Hello everyone and welcome to our podcast Uncuff India by One Future Collective. My name is Sanchi and…

Uncuff India Episode 9: Civic space and dissent: A pathway to social justice

January 10, 2024As protests by civilians continue and are forcefully suppressed, it becomes essential to confront the state's response to dissent. This…

One Future Post Volume 7: Feeling Natural

January 5, 2024Dear One Future Community, The end of 2023 seemed to weigh heavy on us. As the ongoing genocide tightens its…

Uncuff India Episode 8: Global affinity towards right wing governance: co-creating a civil society

December 14, 2023In this episode, we explore the global rise in right wing governance and what this translates into for social justice…

Uncuff India Episode 7: Resisting gender-based violence by armed forces

November 23, 2023Through this fresh episode of Uncuff India, we attempt to understand the differential impact of armed violence on women and…

Resting in the Resistance of Poetry

November 6, 2023Curator's note In this poetry series, I have attempted to explore the relationship I share with poetry. I find poetry…

Uncuff India Episode 5: Caste violence, resistance and justice

October 11, 2023Episode 5: Caste violence, resistance and justice Through the fifth episode of the podcast, we aim to unpack caste violence,…

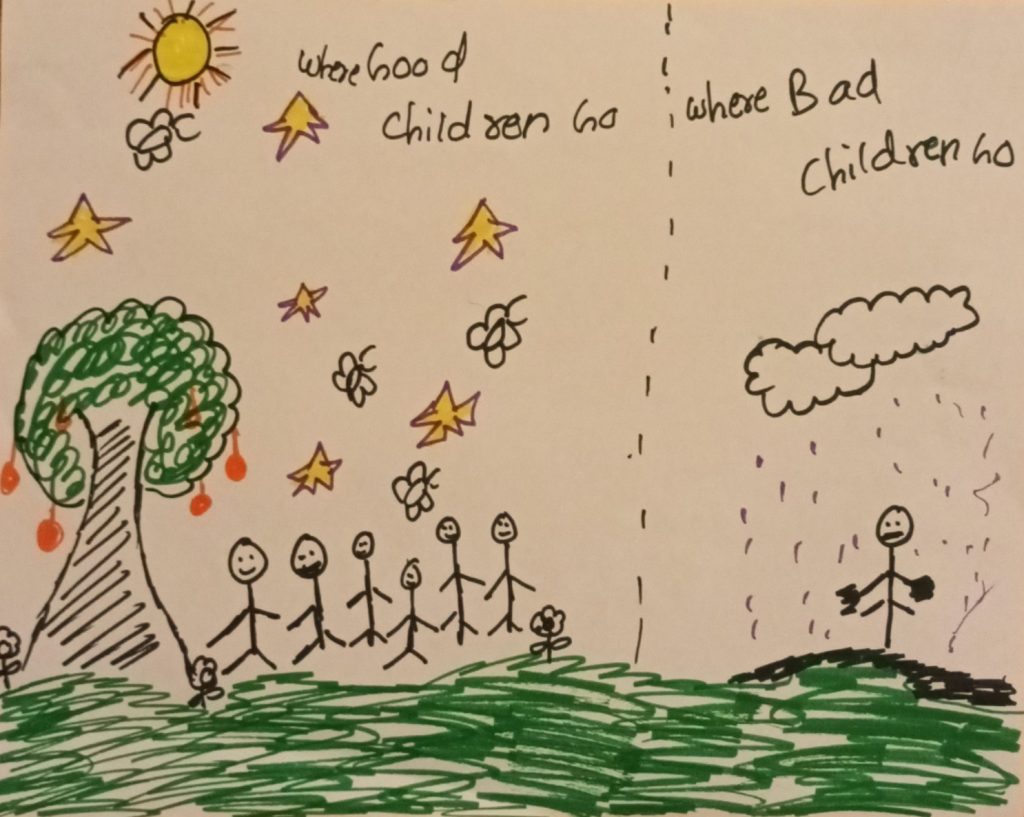

Growing up on the other side of Childhood

October 3, 2023mummy, you once said that all things have their place in this world: bicycle wheels spinning aimlessly in the afternoon…

Uncuff India Episode 4: Invisible Wars and Vulnerability in Kashmir

September 27, 2023Episode 4: Invisible Wars and Vulnerability in Kashmir This episode examines the nature and sites of warfare and the changing…Explorations on Feminist Leadership | S1: Episode 7

September 15, 2023Episode 7: Safety in Educational Spaces The way educational spaces are conceptualized and the way they operate is with the…

Donate Now

Get Involved